An FBI raid on a reporter’s home shows the problem with biometrics

Quick Look

• The FBI raid on Washington Post reporter’s home shows uncertainty about biometrics under the Fifth Amendment.

• Hannah Natanson was compelled to unlock a MacBook with her fingerprint.

• Until the law is clarified, use PINs/passwords instead of biometrics.

Recently, the FBI served a search warrant on the home of Washington Post reporter Hannah Natanson.

It's rightfully being decried as yet another disturbing attack by the Trump Administration on America's tradition of free and independent press—a tradition that was dealt yet another blow this week when the Administration arrested four Black journalists in Minnesota, one of whom was former CNN anchor Don Lemon.

While much ink has been spilled about the potential chilling effect the raid on Natanson's home may have, some key details of the search are now coming to light.

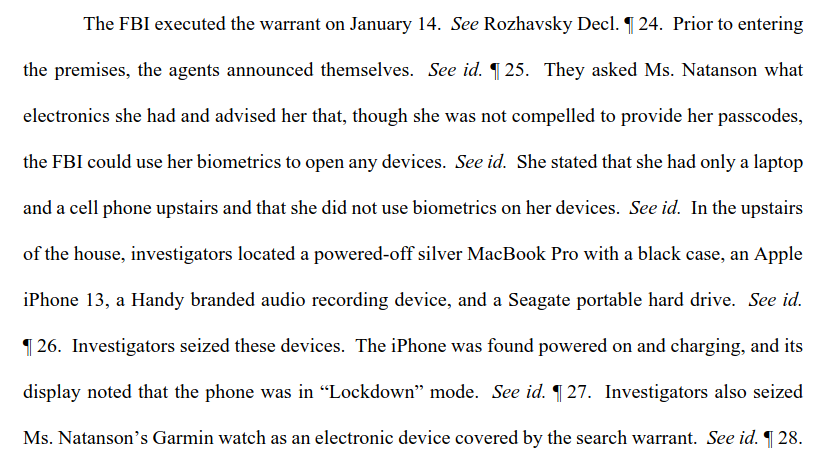

Authorities seized several devices from Natanson's home

While the seizures raise a number of concerns, perhaps overlooked is that Natanson was compelled to unlock one of her MacBook computers using her fingerprint.

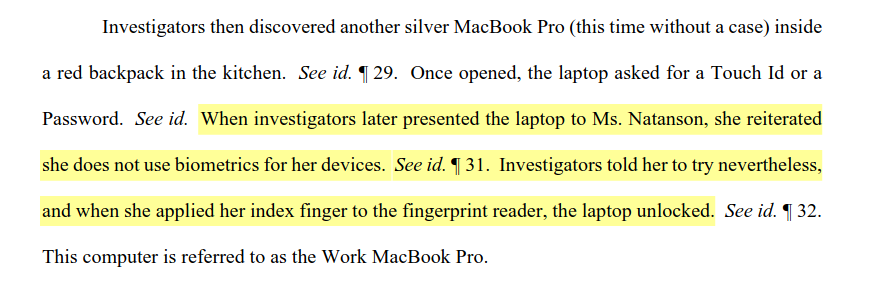

Authorities compelled Natanson to unlock her device

The warrant used by authorities to search Natanson's home explicitly stated that agents could compel her to unlock her devices using biometrics, such as a fingerprint or face scan, but they could not compel her to reveal any passwords.

Yet, as the search continued, authorities eventually discovered a second computer inside a red backpack in her kitchen.

When agents opened the computer, the lockscreen prompted them to enter a password or use TouchID. The agents then insisted—perhaps against the orders of the search warrant shown above—that she attempt to unlock the device.

The government states that Natanson put her index finger on the scanner, which then unlocked it.

Can you be compelled to unlock your device with biometrics?

This is the exact issue the Decent Project wrote about a little more than two weeks ago.

In our article entitled Should you use biometrics on your phone?, we explored the murky legal landscape over whether law enforcement can compel someone to unlock their device using their fingerprint or face.

Currently, courts are split on the issue. It comes down to whether a court sees the use of biometrics as “testimonial” evidence.

Testimonial evidence is generally anything that requires you to divulge the contents of your mind, i.e. things you know, have seen, or have heard. This kind of evidence has a long tradition of being protected by the Fifth Amendment's privilege against self-incrimination, meaning you cannot be compelled to reveal it.

However, some courts do not think that biometrics are “testimonial” in nature. Instead, they argue a biometric unlock doesn't reveal anything about the content of an individual's thinking or knowledge.

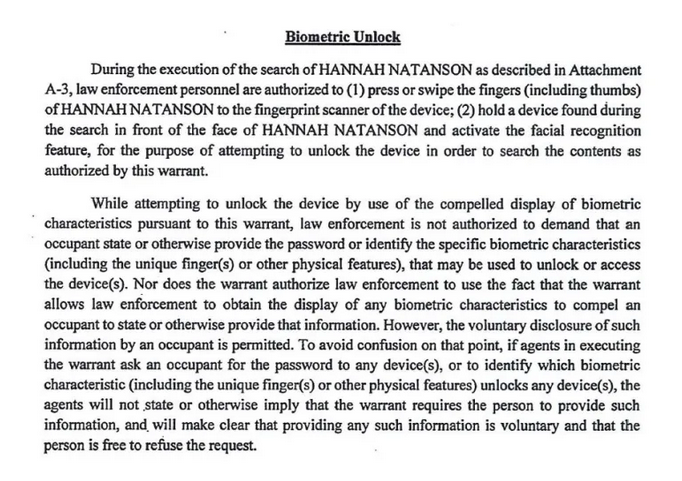

For example, in 2024, the 9th Circuit (in purple above) said in United States v. Payne that biometrics are not afforded the same protections as passwords or PIN numbers:

“While providing law enforcement officers with a combination to a safe or passcode to a phone would require an individual to divulge the 'contents of his own mind,' turning over a key to a safe or a thumb to unlock a phone requires no such mental process.”

We at the Decent Project strongly disagree with this view, and we think Natanson's case is a great example as to why.

What Natanson's fingerprint actually revealed

When Natanson unlocked the MacBook in her kitchen, it revealed several things about her and her relationship to that device.

First, it demonstrated that Natanson knew how to biometrically unlock the device.

This, in our opinion, stands in direct contrast to the 9th Circuit's view that unlocking a device with your finger “requires no ... mental process.”

The government's filing isn't particularly clear on the exact exchange, but when agents “told her to try” to unlock the device and she did so with her index finger, it raises the question: how did she know which finger to use?

Second, her fingerprint demonstrated her control over the computer.

Unlocking a device with your fingerprint is a pretty clear indication that you are the owner of that device, or at least in control of it. If this device is not a shared computer, then it effectively demonstrates that Natanson is responsible for the content found on the device.

It's important to note that Natanson is not a defendant in this case, nor is she a target of the investigation—but in any other context, this kind of evidence could be damning.

Instead, imagine if authorities had found the computer in Natanson's home and it did not have TouchID. Since Natanson cannot be compelled to reveal a PIN or password, what would authorities have to demonstrate that the device is hers?

They could say the device was in her kitchen and that it was found in her backpack, but that's about it.

Takeaway

Not all courts agree with the 9th Circuit when it comes to biometrics. As discussed in our earlier article, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last year that biometrics can be afforded the same protections as other testimonial evidence.

While that's good news, this issue is new and the law is still developing. As such, unless and until there is legal clarity, the Decent Project continues to recommend that individuals do not use biometrics on their devices.

~ Torman

Verify this post: Source | Signature | PGP Key

#privacy #security #OPSEC #FifthAmendment

If you enjoyed reading this or found it informative, please consider subscribing in order to receive posts directly to your inbox:

Also feel free to leave a comment here: Discuss...